Jake Grieves-Cook, the founder of Gamewatchers Safaris & Porini Camps, has been involved in Kenya’s tourism and wildlife conservation scene for over 40 years. Here he describes the background to the setting up of four conservancies together with the Maasai landowners, with the aim of protecting the wildlife habitat which would otherwise have been fragmented …

“Conservancies: Helping Reverse Habitat Loss” by Jake Grieves-Cook

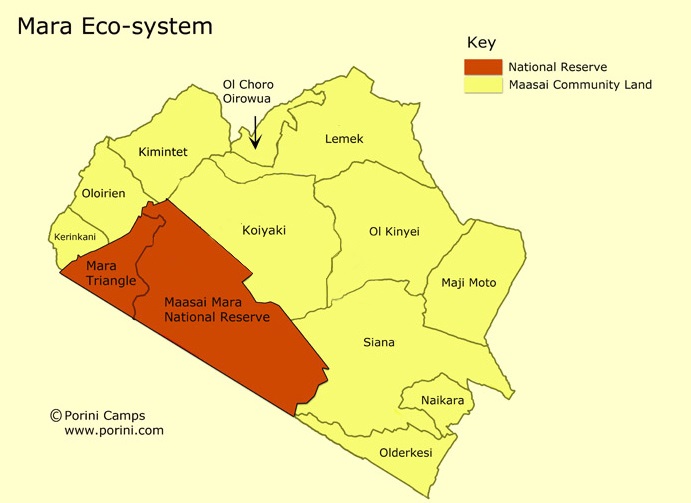

Today the Conservancies are almost the only areas of intact forest and open grassland plains left in what was the greater Mara eco-system, outside the Mara Reserve, as the area beyond the official Reserve is now increasingly fenced, fragmented and settled, presenting a threat both to traditional pastoralism and to wildlife. The success of the Conservancies in protecting habitat provides a model which could be applied to supporting pastoralism in parts of the remaining million acres of sub-divided lands in the former Mara eco-system.

Pastoralism and wildlife in the early days

The Maasai people have occupied the savannah grasslands of Southern Kenya and Northern Tanzania for centuries. In the past, their traditional form of nomadic pastoralism meant that a relatively small population of Maasai moved their large herds of hardy Zebu cattle over a vast rangeland to follow the rainfall and to practise rotational grazing which conserved the grass.

Their warlike warriors, il murran, were the guardians of their landscape. Their custom of cattle raiding, combined with their aversion to the presence of any outsiders on their lands, kept the rangelands free from settlement or incursions by other communities. This ensured that there was more than adequate pasture for their livestock. This form of pastoralism conserved the rangeland and at the same time was beneficial to the wildlife living on the savannah plains of East Africa alongside the Maasai and their livestock.

With two rainy seasons a year, unlike the drier regions of Southern Africa, the Serengeti-Mara ecosystem was able to support an enormous biomass of wild herbivores as well as the predators that lived off them. The Maasai had a taboo against eating wild animals and subsisted entirely on their livestock, so consequently the wildlife thrived. It was only lions which might be speared occasionally in retribution when they made the mistake of killing a cow, or a male lion might be a target of warriors on a lion hunt, olamayio, a rite of passage in a warrior’s life.

Group Ranches in the Mara and the beginnings of Tourism

Wildlife tourism to the area started to make its mark from the early 1960s when the Maasai Mara National Reserve was established and the first safari lodge, Keekorok, was opened to cater for the growing number of visitors who drove around in zebra-striped minibuses to photograph the teeming animals on the Maasai plains.

Around the same time the government passed the Land (Group Representative) Act 1968 which established what were known as “Group Ranches”, dividing the greater Mara area outside the Reserve into large tracts of land allocated to the local communities. The plan was that the members would be able to manage the grazing within their own group ranch, giving all members access to pasture, including those who were poorer. The main objective in having the group ranches was rangeland conservation through increased livestock off-take, with the aim of increasing income to the pastoralists through beef production and sales of cattle.

It was hoped that the group ranches would regulate herd sizes. However this did not materialise as all the individual members wished to maximise their herds and just ignored the stock quotas. They were not market-orientated and tended to sell the minimum number of animals just to meet their financial commitment to be members of the Group Ranch. Livestock numbers quickly increased beyond the carrying capacity of the land and pasture became degraded through continual over-grazing. The objective of preventing environmental degradation, by reducing the overgrazing, could not be achieved and in due course there was growing pressure from the membership to sub-divide the land and to issue title deeds to the individual members so that each member could own a parcel of land.

MAP 1: THE FORMER GROUP RANCHES IN THE MARA ECO-SYSTEM

Prior to sub-division taking place, there were a number of Maasai ranches which earned an income from tourism. One of the first to do so was Ol Choro Oirowua, followed by Lemek Group Ranch and Koiyaki Group Ranch (see map above).

The landowners allocated campsites to commercial safari operators and earned an income by charging a fee for each tourist through the sale of tickets for visitors who were brought in by the safari operators to be driven around on “game drives” to view wildlife in designated areas within a Group Ranch. There were some complaints that the income from ticket sales was not being distributed to the Group Ranch members by the committees and this coincided with calls for the Group Ranches to be sub-divided, as many members were dissatisfied and preferred to be allocated their own plots of land.

Research shows that mismanagement was a key issue: “The group ranch committees had difficulties acting as collective bodies; they tended not to meet, rarely reached important decisions, and then failed to implement their decisions. As a result, dips, water pumps and engines were not properly managed and maintained, livestock quotas were not enforced, and revenue was not collected for repayments of outstanding loans.” (Peter Veit)

Sub-division of Group Ranches

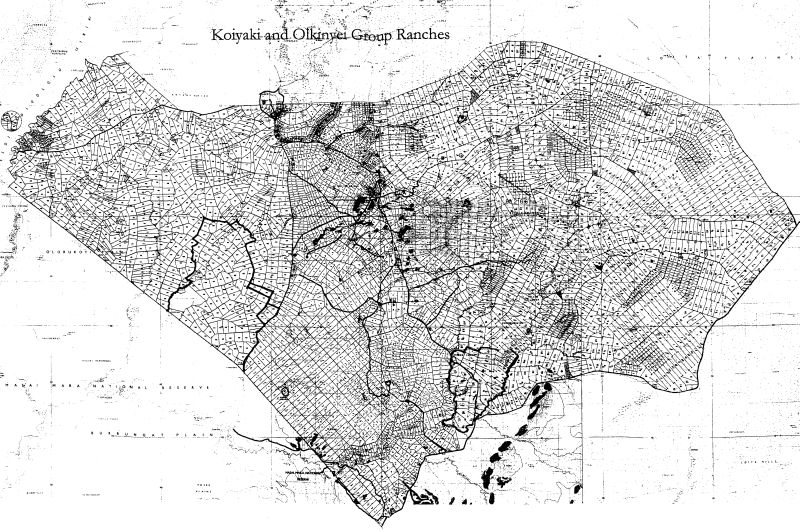

The pressure mounted to split up the Maasai Group Ranches for a number of reasons. As mentioned, many ranch members were frustrated with the inefficient management of the ranches by committees while others wanted to have land title deeds to use as security to obtain bank loans. Some of the sons of the ranch members wished to have their own plots of land rather than waiting to inherit a share of their fathers’ land. The government agreed to allow sub-divison and surveys were carried out after which the ranches were split up and title deeds allocated to all the individual members. The map below of Koiyaki and Ol Kinyei shows how those two Group Ranches were subdivided into small parcels, usually plots of 100 to 170 acres, owned by over 3,000 individuals.

MAP 2: THE FORMER KOIYAKI AND OLKINYEI GROUP RANCHES SUB-DIVIDED INTO THOUSANDS OF PLOTS

Leasing land to form Conservancies

There were concerns that the sub-division of the Koiyaki Group Ranch would result in fragmentation of the lands adjacent to the Reserve and the immediate loss of wildlife habitat which would cause a decline in wildlife species, just as had already happened in other places once they were sub-divided and parcelled out to individual owners. Some Maasai leaders, together with private sector safari operators with an interest in conservation, felt that there was an opportunity to conserve this habitat to create wildlife sanctuaries which could generate an income for the landowners from tourism.

There was also a need to find a way for the communities to earn an income from tourism in a way that would avoid the rapid over-development of tourist accommodation facilities which had taken place in recent years with more and more camps springing up inside the Reserve and along the boundaries especially in Talek, Sekenani and Siana as well as ribbon developments along the Mara River outside the Reserve. In the 1960s there was only one lodge and 128 beds in the Mara Reserve but by 2006 this had grown to over 100 camps and lodges with over 5,000 beds and this was still growing at a rapid pace. This resulted in high density tourism with too many safari vehicles crowding the animals, spoiling the visitor experience and damaging the environment.

The solution which we proposed was to create wildlife conservancies on the land nearest to the Reserve by leasing the adjacent parcels of land to from wildlife conservancies to be used for safari tourism as an alternative form of land use for the owners. To avoid high density tourism we devised a formula of no more than 1 tent per 700 acres with a limit of no more than 12 tents in any camp and a maximum of 1 vehicle per 1400 acres within conservancies of at least 7000 acres in area as a minimum.

To maximise the income of the landowners and to avoid fluctuations when tourism suffered setbacks or had low seasons, the payments were based on a rent per acre instead of a payment per tourist as had been done in the past on the Group Ranches and in the Reserve.

It was already evident that the effect of a payment per tourist meant that there would always be pressure from those receiving the payments (the County Council which managed the Reserve or the former Group Ranch committees) to have more tourists by increasing the numbers of tourist beds and having more camps and lodges, resulting in overcrowding. So by switching to a payment per acre and putting a maximum limit on the number of beds, it was possible to have low density tourism while still paying an agreed total amount to the landowners based on the acreage regardless of the occupancy levels of the camps.

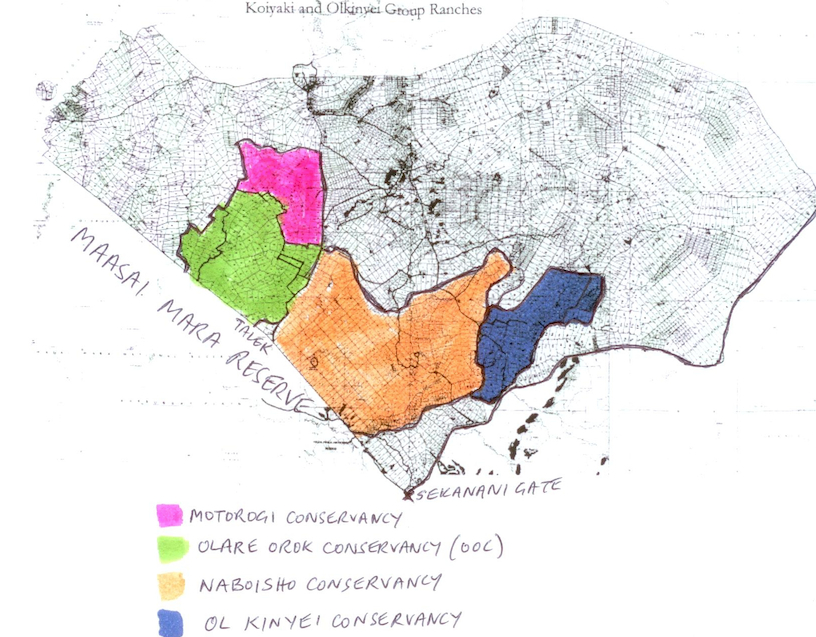

Payments would be made direct to the individual landowners at the same amount per acre, resulting in a transparent arrangement where everyone knew exactly what was being paid to all the members of the Conservancy. This formula was followed in 4 conservancies set up on land leased from the individual landowners whose plots were put together to establish Ol Kinyei Conservancy, Olare Orok Conservancy, Motorogi Conservancy and Naboisho Conservancy (see map below).

MAP 3: PLOTS OF LAND LEASED TO FORM FOUR WILDLIFE CONSERVANCIES

Positive effects of Conservancies:

- No more over-grazing of the land in the conservancy

- No human settlement, sedentary homesteads or livestock bomas in the conservancy

- Land improves, vegetation and grass regenerates, no tree-cutting, cultivation or ploughing

- Virtually no poaching or wildlife killing within the community-owned conservancies

- Payments received directly by individual landowners, NOT via a committee with chance of money going astray

- Employment opportunities: the camp staff, guides and conservancy rangers are all drawn from the families of the Maasai landowners

- Opportunity for involvement / participation of landowners in tourism

- Koiyaki Guiding School: training for school-leavers who can have a career in their conservancies

- Continued ownership of land by the individual title deed holders

- All conservancy members have opened bank accounts to receive their monthly lease payments. This is significant as it means these community members are now shifting to a cash-based way of life rather than using their herds as the sole repository of their wealth.

- It has become apparent that conservancy members own significantly less livestock than non-members so that participation in conservancies might be causing a reduction in the herd size of conservancy members

- Improved tourism – small scale, emphasis on the safari experience, with qualified Maasai guides holding KPSGA certification

- Eco-friendly form of tourism – solar energy, sewage management, refuse disposal all certified by Ecotourism Kenya and the camps have silver certification.

- Wildlife viewing without the crowds of minivans

- High density of wildlife: highest concentration of wild lions in Africa

- Big increase in wildlife numbers in the Conservancies

- Excellent Customer feedback – highly rated by visitors: Number 1 on TripAdvisor

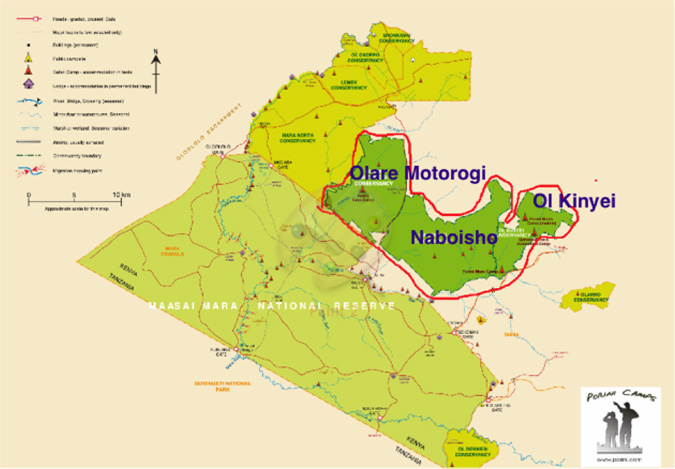

Olare Orok and Motorogi were merged to form Olare Motorogi Conservancy which together with Naboisho and Ol Kinyei comprise 100,000 acres of protected wildlife habitat, all following the formula of maximum 1 tent per 700 acres. In addition, other Conservancies have been set up in the outer Mara, further expanding the protected area, such as the 74,000 acre Mara North Conservancy.

MAP 4: 100,000 ACRES OF PROTECTED HABITAT ADJACENT TO THE MARA RESERVE

Impacts of Sub-division

As had been predicted, within a short time after sub-division the land became increasingly fragmented. The sub-division of this vast area into thousands of small plots owned by individuals has meant that the traditional nomadic pastoralist lifestyle of the local Maasai people is having to change. Pasture land and communal grazing areas are being lost as they become individually owned, fenced off, sold to developers and speculators, or turned into sprawling peri-urban settlements and trading centres. Livestock herders no longer have the same areas available for their cattle to graze and are being forced to look for free grazing in the Reserve and the Conservancies. More and more fences are going up, cutting off wildlife migration and preventing livestock movement onto individually owned land.

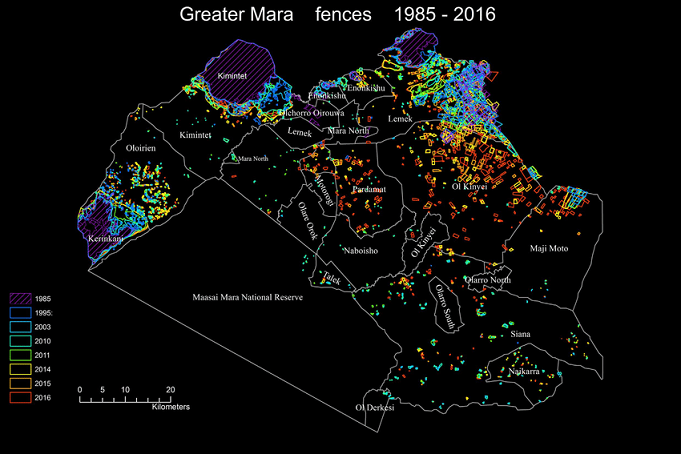

A recent paper headed “Fencing bodes a rapid collapse of the unique Greater Mara ecosystem” by Mette Løvschal, of Aarhus University, and others makes clear just how serious the situation is: “The rapid acceleration in fencing from 2014 is presently threatening to lead to the collapse of the unique ecosystem of the Greater Mara within a few years. The impending cultural consequences of this loss of area may be that pastoralism and a semi-nomadic lifestyle can no longer be sustained. Ecological consequences already involve the decline of wildlife populations and may also result in the collapse of migrating megafauna populations, with secondary consequences for the rest of the ecosystem.”

MAP 5: RAPID SPREAD OF FENCES IN GREATER MARA (Aarhus University. Løvschal, M. et al. 2017)

The Way Forward

We need to focus on how best to assist pastoralists to provide for their families and to have a better quality of life such as by adopting improved systems of livestock rearing to enable them to become commercial meat producers. Modern methods of livestock husbandry could allow them to earn an income from serving the huge external markets outside Kenya as well as the local domestic markets within this country. The first challenge is to change the mindset so that there is an acceptance that stock should be reared to be sold as a product instead of being accumulated as wealth in the form of ever-increasing huge herds way beyond the carrying capacity of the over-grazed land.

There is also a need for education of the children of the herdsmen’s families so that they can have other employment opportunities and careers in the future beyond only herding the family goats and cattle. Education is important and it should be noted that the Conservancies are contributing to schools and supporting parents in paying school fees through bursaries. Tourism and conservancies can offer jobs and provide careers for more school leavers from the local community giving them alternative ways of earning livelihoods.

What is urgently needed is for areas to be set aside now to protect livestock rangeland for cattle in the same way that the conservancies have been established for wildlife. Unless this is done now, there will soon be nowhere left for many of the Maasai livestock owners to use for grazing by their herds of cattle, sheep and goats. This will cause a huge pressure on the wildlife habitat in the Mara Reserve and the new conservancies with the very real threat of serious environmental degradation through over-grazing by livestock in the remaining areas available to them.

Lessons can be learnt from the failures of the Group Ranches to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past. The conservancy movement has shown how savannah grassland can be conserved and set aside for wildlife to generate an income and livelihoods for the landowners. We need a similar movement to conserve pastureland for the Maasai livestock so that we do not end up with a situation where the only grazing left is in the Conservancies that were set up specifically to be protected wildlife habitat. There is also a need for changes to the form of livestock husbandry with a greater emphasis on smaller herds but higher quality livestock and use of feedlots and hay as an alternative to nomadic grazing.

Find Out More:

Recommended Accommodation:

Porini Amboseli Camp, Selenkay Conservancy

Porini Rhino Camp, Ol Pejeta Conservancy

Porini Mara Camp, Ol Kinyei Conservancy (Mara)

Porini Lion Camp, Olare Motorogi Conservancy (Mara)